We live in a photo-centric world. There’s no doubt about that. We voluntarily chronicle just about every aspect of our lives, thanks in part to the proliferation of image-based social-sharing applications like Instagram, Facebook, Snapchat, and TikTok. “If it’s not on social media, did it ever really happen?” is sort of the unofficial mantra of today’s über-connected population.

It’s kind of hard to imagine a time when people weren’t walking around with cameras at their side at all times. But it really hasn’t been all that long. Camera phones have only been around for just shy of 20 years, debuting June of 2000 in South Korea. Photography in general has only been with us for about 200 years, a mere blip on the timeline of human history.

In those 200 years, so much happened with regards to advancements in the field, from inception until now. But how did it all begin? Most people with at least a broad understanding of its history would probably recognize the daguerreotype as the grandfather of modern photography. Invented in 1839 by Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre, this was indeed the first public-facing, commercial means of capturing images. However, the first-ever surviving photo taken was developed — using a different technique — more than a decade earlier by another Frenchman, Nicéphore Niépce.

Niépce created a process he called heliography, or “sun drawing,” which used a triad of tools to “snap” photos: a camera obscura, a pewter plate, and natural light. He captured this first image with an exhaustive exposure time of — wait for it — eight hours. The result (View from the Window at Le Gras, below) was a grainy, barely perceptible (by today’s standards), black-and-white scene looking out a window of the inventor’s home. And it changed everything.

As big a breakthrough as this was, suffice it to say, it never really took off. Not only was it a painstakingly lengthy undertaking, Niépce was also famously protective of the secrets of his method. But still, it certainly paved the way for the future. In fact, it was Niépce’s collaboration with Daguerre that helped the latter bring his more commercial process to fruition, though the former did not live long enough to see its debut into the world. The daguerreotype shortened exposure time to a mere 15–30 minutes. (And you thought getting the kids to sit still for a family portrait was a struggle today!)

While the daguerreotype resulted in moderately crisp-looking imagery, developing onto metal plates didn’t exactly make for the most cost-effective or easy-to-reproduce prints. Enter the calotype, a method created by British inventor William Henry Fox Talbot in 1841. The calotype traded the metal plates for light-sensitive paper that sacrificed some photo quality for ease of production.

But it was the invention of flexible roll film, popularized by George Eastman in the late 1880s, that really took photography to a whole new level. Eastman used this creation to hock the first Kodak camera (yes, that Kodak) to aspiring amateur photographers, using the slogan, “You press the button, we do the rest.” Photography was suddenly much more accessible and easily portable, though it still came at a hefty price. The 100-exposure camera sold for $25 or roughly $630 by today’s standards, plus it cost another $10 (~$250 today) for development.

Since then, the camera has made leaps and bounds likely beyond anything Niépce could have ever imagined. Now, it’s de rigueur for us all to own slim, pocket-sized “cameras” that are also capable of communicating with people across the globe in real-time. What was once a cumbersome, costly novelty available to few is now something we really don’t think twice about. We record virtually every waking moment in our lives, thanks especially to our social networks, which invite people to glimpse even the most mundane of details in our daily routines.

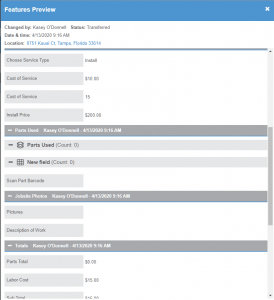

Photography is even an integral part of business practices everywhere now. Maintaining photo records of projects particularly benefits many field work–focused companies. Images of finished projects can be used to build a robust portfolio to attract new customers and grow business. Before-and-after photos can serve as visual evidence of services rendered and the condition of objects at the start of a job.

So having photo-capturing capabilities built into our software isn’t just some flossy feature that looks good on paper. This functionality has a very real purpose. It saves time and money on multiple fronts, and it makes paperless forms much more robust, with richer, meaningful content. Having it integrated with our forms keeps all related projects perfectly sorted to avoid the mix-up that could easily happen when pairing paper forms with a non-integrated camera.

It’s probably safe to say that neither Nicéphore Niépce, nor Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre, nor William Henry Fox Talbot ever imagined that their forward-thinking innovations would lead us to where we are now. (What might they think about Instagram?) But we’re sure glad they played their part in getting us here.

Have any questions on how Actsoft can help you?

Share this post:

About the author : Joshua Pramis

Joshua Pramis is a writer and editor with an affinity for all things travel, tech, and food. His work has appeared on Travel + Leisure, Conde Nast Traveler, Digital Trends, and the Daily Meal, among other outlets. When he's not at home canoodling with his cats (which is typical), you'll find him running races, exploring new locales, and trying out different food venues in St Petersburg, Florida.

Encore & Geotab Drive

Encore & Geotab Drive

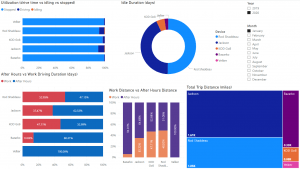

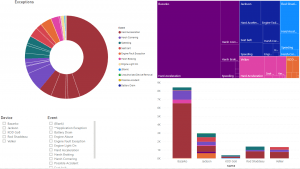

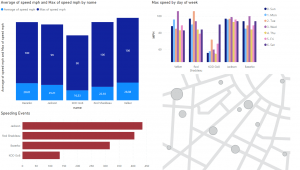

Gain even greater insight into the daily activities of your fleet using the combination of Geotab and Actsoft. Geotab devices provide detailed data collection and seamless integration with our solutions; learn more about the ways your vehicles are being used daily with the power of this tandem.

Gain even greater insight into the daily activities of your fleet using the combination of Geotab and Actsoft. Geotab devices provide detailed data collection and seamless integration with our solutions; learn more about the ways your vehicles are being used daily with the power of this tandem.

Actsoft partnered with Odin to provide our solutions overseas, through payment processing integrations. Odin helps us support user management for our software; customers can also purchase our products through Odin’s billing platform.

Actsoft partnered with Odin to provide our solutions overseas, through payment processing integrations. Odin helps us support user management for our software; customers can also purchase our products through Odin’s billing platform.

VisTracks powers our Electronic Logging Device (ELD) solution, which enables transportation businesses to easily automate their hours of service logs, remain in governmental compliance, and reduce their potential to incur costly fines.

VisTracks powers our Electronic Logging Device (ELD) solution, which enables transportation businesses to easily automate their hours of service logs, remain in governmental compliance, and reduce their potential to incur costly fines. Integration between Actsoft solutions and BeWhere’s software products is available. Take your team’s asset tracking, cellular data connectivity, and field insight a step further with effective, cross-application compatibility.

Integration between Actsoft solutions and BeWhere’s software products is available. Take your team’s asset tracking, cellular data connectivity, and field insight a step further with effective, cross-application compatibility.

CalAmp tracking devices for vehicles and assets alike are compatible with Actsoft solutions, making it easy for you to efficiently monitor your equipment and fleet cars. Help your team enhance accountability, safety, and savings through a combination of easily installed hardware and intuitive software.

CalAmp tracking devices for vehicles and assets alike are compatible with Actsoft solutions, making it easy for you to efficiently monitor your equipment and fleet cars. Help your team enhance accountability, safety, and savings through a combination of easily installed hardware and intuitive software. Our partnership with Uniden is ideal for companies looking to gain advanced diagnostics on their fleets. Uniden’s extensive product listing of car electronics like radios, dash cams, radar detectors, and in-vehicle communicators work in concert with Actsoft’s solutions to better connect your vehicles to the company headquarters.

Our partnership with Uniden is ideal for companies looking to gain advanced diagnostics on their fleets. Uniden’s extensive product listing of car electronics like radios, dash cams, radar detectors, and in-vehicle communicators work in concert with Actsoft’s solutions to better connect your vehicles to the company headquarters. Kyocera offers a wide range of mobile devices, ranging in design from traditional phones to ultra-durable handset technology. Actsoft is able to equip organizations in a variety of different industries with solutions for improved business, while Kyocera supplies the technology they can flawlessly operate on.

Kyocera offers a wide range of mobile devices, ranging in design from traditional phones to ultra-durable handset technology. Actsoft is able to equip organizations in a variety of different industries with solutions for improved business, while Kyocera supplies the technology they can flawlessly operate on.

Our software is the perfect complement to Apple’s user-friendly technology. Equip your workforce with the devices and solutions it needs for optimized productivity during daily operations with Apple and Actsoft.

Our software is the perfect complement to Apple’s user-friendly technology. Equip your workforce with the devices and solutions it needs for optimized productivity during daily operations with Apple and Actsoft.

Actsoft and Sanyo teamed up to merge intuitive business management software with the technology of today. This partnership allows us to provide you with all the tools your team needs for improved workflows, better coordination, and optimized productivity.

Actsoft and Sanyo teamed up to merge intuitive business management software with the technology of today. This partnership allows us to provide you with all the tools your team needs for improved workflows, better coordination, and optimized productivity. Motorola’s mobile technology works in tandem with our solutions to provide extra versatility to your business practices. Coupled with our software’s features, Motorola’s reliable devices make connecting your workforce simpler than ever to do.

Motorola’s mobile technology works in tandem with our solutions to provide extra versatility to your business practices. Coupled with our software’s features, Motorola’s reliable devices make connecting your workforce simpler than ever to do. We’re able to bundle certain solutions of ours (including our Electronic Visit Verification options) with Samsung devices to help your team achieve as much functionality as possible, while keeping rates affordable. Use these combinations for accurate recordkeeping, improved communication, and smarter data collection in the field.

We’re able to bundle certain solutions of ours (including our Electronic Visit Verification options) with Samsung devices to help your team achieve as much functionality as possible, while keeping rates affordable. Use these combinations for accurate recordkeeping, improved communication, and smarter data collection in the field.